Weeknote 19 – 22

- Bit delayed with these.

- We got married last week, kept it comparatively low-key (registry office followed by the pub next door, then a bigger party one of our local bars here in the Wick) and we had a fucking blast 1.

- Had a bit of an emotional comedown after it. I’ve never got it before when people said London is a lonely city — that the high rent and low pay and the way public transport only functions for commuting to and from the oligarch ghost-town of central mean that you don’t ever get to see your friends. I mean it probably helped that both the BBC and GDS were/are filled with people I genuinely consider to be my friends. But after the wedding it really stuck me how many wonderful people I have in my life that I barely get to see.

- Need to figure out how to change that up.

- Most importantly, I wore 2 an ecru Le Laboureur jacket, a thigh-length white COS buttondown over some Miami Vice recreation white pants from Zara and some cream leather Adidas high-tops. Obviously I appreciate the lads at Hypebeast marking it as their look of the week.

- Back to normal business, over the last couple weeks I’ve fallen in love with Simon Reynolds term ‘the prog fallacy’, which I found in this old Pitchfork list of the best 50 IDM albums.

For as a guiding concept, IDM raises way more issues than it settles. What exactly is 'intelligence' as manifested in music? Is it an inherent property of certain genres, or more about a mode of listening to any and all music? After all, it’s possible to listen to and write about 'stupid' forms of music with scintillating intellect. Equally, millions listen to 'smart' sounds like jazz or classical in a mentally inert way, using it as a background ambience of sophistication or uplifting loftiness. Right from the start, IDM was freighted with some problematic assumptions. The equation of complexity with cleverness, for instance — what you might call the prog fallacy.

[...]

Most of these IDM artists knew each other socially and sometimes collaborated. All were British.

Simon Reynolds for Pitchfork

- Leads nicely into this Atlantic article about how Mckinsey destroyed the middle class. If you’ve ever worked with me or followed me on social media you’ll know my feelings about The Big M, but the article provides a proper thoughtful overview of the damage that their philosophy has done to the world. And there’s always Wikipedia for a taste of their work portfolio

Particular industries, and still more individual companies, may be committed to distinctive, concrete goals and ideals. GM may aspire to build good cars; IBM, to make typewriters, computers, and other business machines; and AT&T, to improve communications. Executives who rose up through these companies, on the mid-century model, were embedded in their firms and embraced these values, so that they might even have come to view profits as a salutary side effect of running their businesses well.

When management consulting untethered executives from particular industries or firms and tied them instead to management in general, it also led them to embrace the one thing common to all corporations: making money for shareholders. Executives raised on the new, untethered model of management aim exclusively and directly at profit: their education, their career arc, and their professional role conspire to isolate them from other workers and train them single-mindedly on the bottom line.

Buttigieg carries this worldview into his politics. Wendell Potter, at The Intercept, observes that 'a lot' of Buttigieg’s campaign language about health care, including 'specific words' is 'straight out of the health-insurance industry’s playbook.' The influence of management consulting, moreover, goes far beyond language to the very rationale for Buttigieg’s candidacy. What he offers America is intellect and elite credentials — a combination that McKinsey has taught him and others like him to believe should more than compensate for an obvious deficit of directly relevant experience.

This is a dangerous belief. Technocratic management, no matter how brilliant, cannot unwind the structural inequalities that are dismantling the American middle class. To think that it can is to be insensible of the real harms that technocratic elites, at McKinsey and other management-consulting firms, have done to

Americathe Planet.

Daniel Markovits for The Atlantic

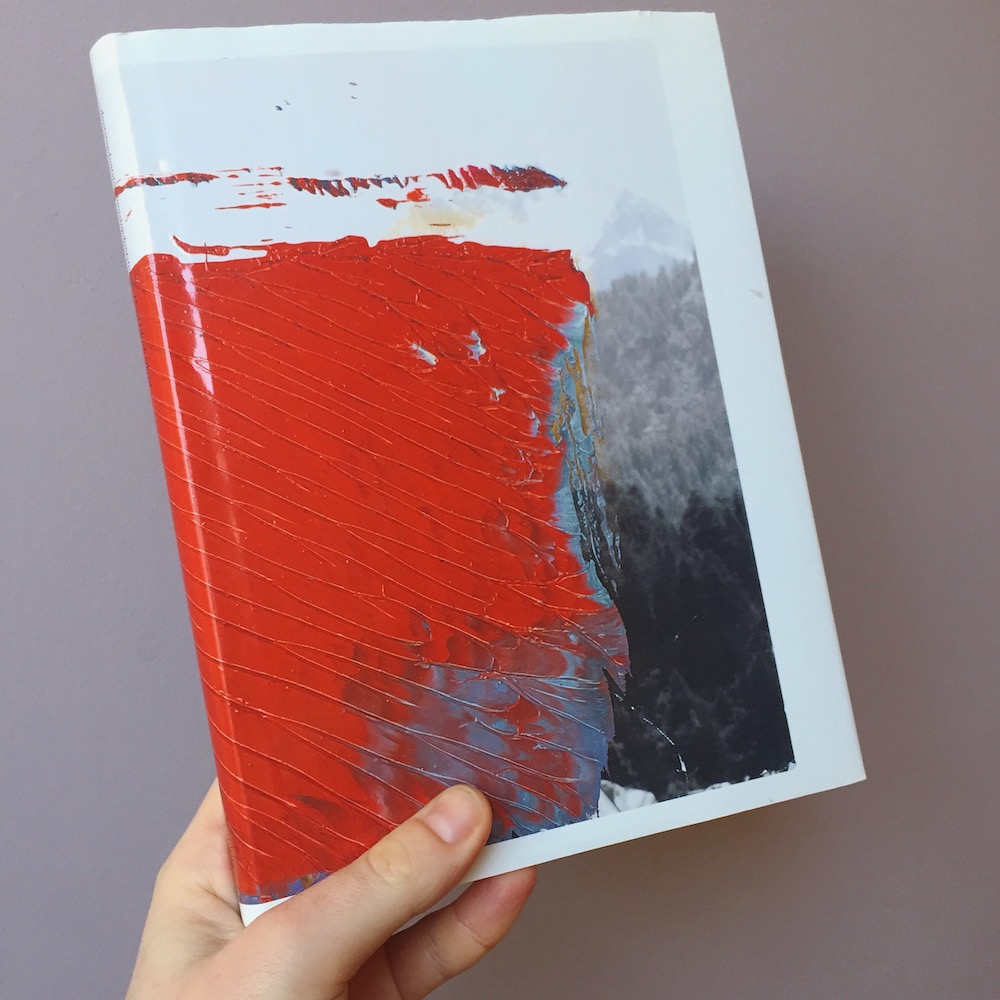

- Last month at the Beautiful Swiss Books thing at Tenderbooks I picked up a copy of Hans Ulrich Obrist’s dontstopdontstopdontstopdontstop in their sale for 3 pounds or so, entirely because the cover is so gorgeous 3.

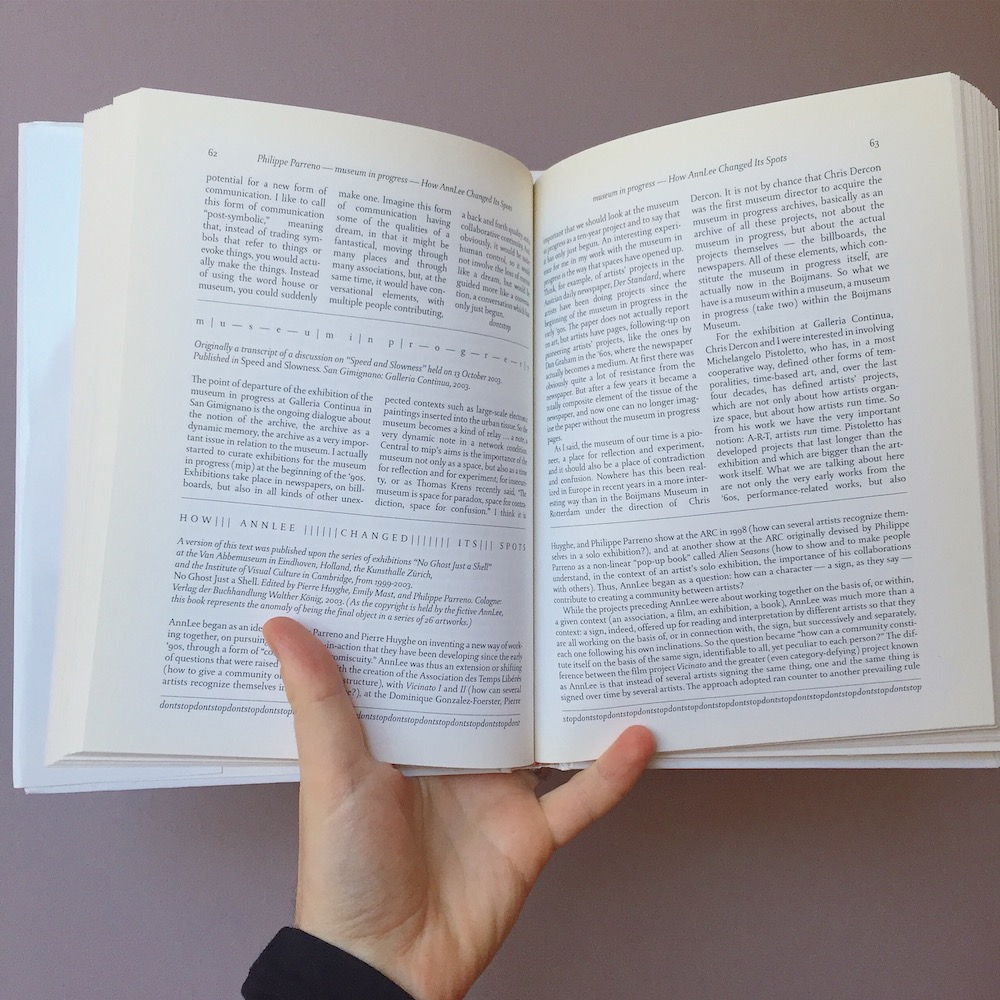

- It’s a proper peak-era M/M (Paris) thing, vibrant embossed Gerhard Richter painting on the dustjacket, complex internal layout experimenting with proto-new aesthetic intertextuality and hyperlinking, but also classically beautiful 4. Almost illegible of course.

- There’s a good piece in it about Cedric Price, an architect I was aware of but didn’t know much about. It talks about his aviary for London Zoo which (apparently though I’ve never noticed this) adapts its shape to the wind. It also describes the original vision for the structure to modify its shape and location to where the birds inside it want to fly. It’s a lovely idea, somehow combining the ideas of user-centred design and modular maker movement into a design strategy that — as Ella put it — avoids the Amazon mistake of assuming you only want to repeat your past behaviours.

- I’m starting to dig into the videos of his lectures floating around online. This one with him at the AA is pretty fun if you can get over his rambling lecturing style 5 (“I believe a lecture should be as interesting to the person giving it as it is excruciating for the audience”) and touches on loads of issues super-relevant to digital design.

- Good design is how it works. But you only notice a design is good because of how it makes you feel as works. This 032c review of a Barbour x Margaret Howell coat captures both sides perfectly 6.

- When I wrote about that Anselm Keifer show last time I hadn’t seen this batshit interview with him. Love it.

'Ich bin der ich bin,' Kiefer said. I am that I am. 'It was what God said to Moses when he asked for God’s name. It is a. … What is it called again? That word?'

'I don’t remember,' I said. 'But I know what you mean.'

He reached for a phone.

'I’ll call a friend,' he said. 'He is a university professor and should know.'

'Hello?' he said and explained the situation.

'Tautology! Of course! Thank you!'

He hung up the phone.

'It is a tautology,' he said.

Shortly after we sat down for lunch, the cook brought in the food and wine, and Kiefer began to talk about flying, which he loved. He always took a helicopter whenever he was going anywhere, he said. It was the simplest option.

'One of the pilots I used the most died later, by the way,' he said. 'In an accident in the Alps. They crashed when they were carrying timber over there.'

For a few seconds we continued to eat in silence.

'Do you have a helicopter?' he said and looked at me.

'No, unfortunately,' I said.

'You should get one!' he said.

Karl Ove Knausgaard for the New York Times

If you want to chat more about stuff like this, send me an email or get in touch on Twitter.

You can pretend it's 2005 and subscribe to my RSS feed

We picked the date because it looked good and wouldn’t cause any US/European formatting confusions

We picked the date because it looked good and wouldn’t cause any US/European formatting confusions  Monochromatic style with clean white and greys

Monochromatic style with clean white and greys  dontstopdontstopdontstopdontstop cover

dontstopdontstopdontstopdontstop cover  dontstopdontstopdontstopdontstop interior

dontstopdontstopdontstopdontstop interior  Cedric Price at the AA

Cedric Price at the AA  The reviewer in his nice coat

The reviewer in his nice coat